By Ms. Bharti Pangtey and Mr. Nakshatra Gujrati, the authors are students of National Law University Odisha

In India’s private equity (PE) landscape, investors typically acquire minority stakes in promoter-led, unlisted companies. This limited equity exposure compels them to secure robust contractual safeguards through a Shareholder Agreement (SHA). These agreements are not just about economic return—they’re essential tools that empower investors to participate in governance and protect their downside risks.

However, the Indian legal regime adds a unique twist: most of these rights are only enforceable if reflected in the Articles of Association (AoA). Here’s a deep dive into the key clauses investors typically negotiate—and how Indian courts have viewed their validity.

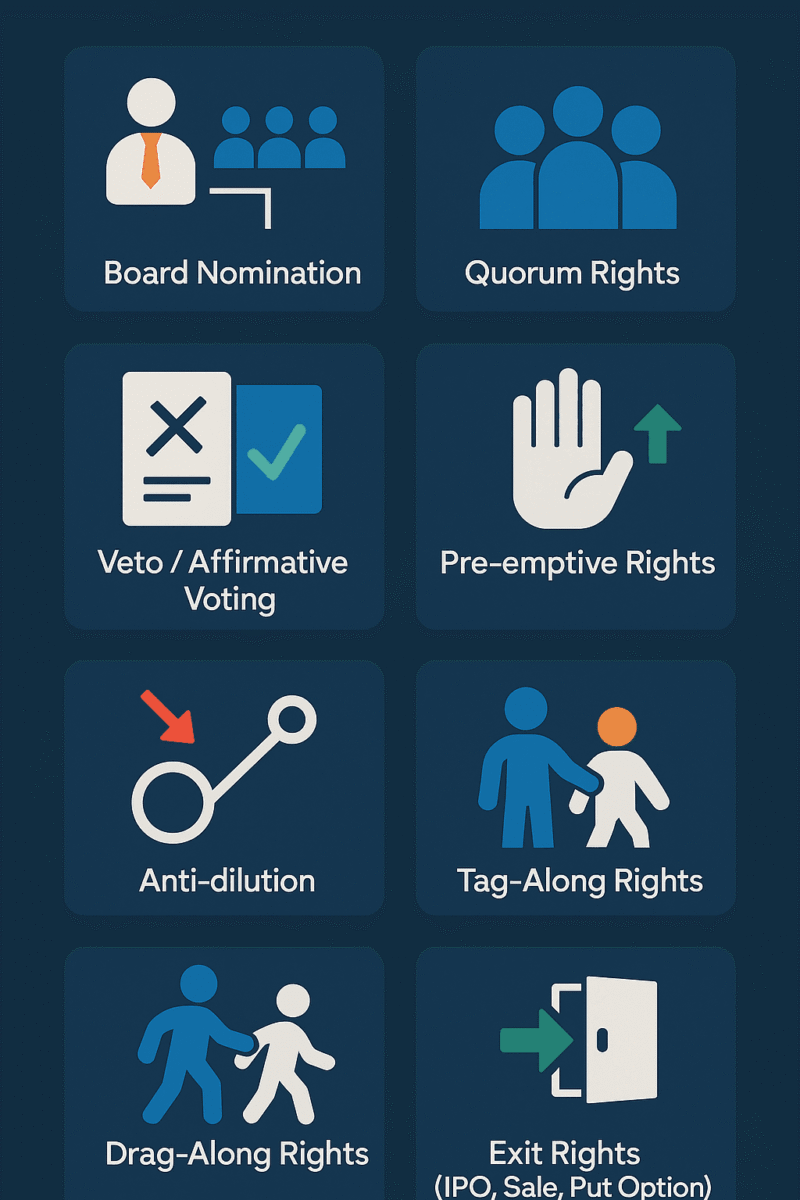

Key Clauses of Shareholder Agreement:

| Clause | Purpose | Detailed Commentary |

| Board Nomination | Ensures investor representation in strategic decision-making. | Indian law allows nominee directors, but enforceability hinges on inclusion in the Articles of Association (AoA). Courts (e.g., Madhu Kapur v. Rana Kapoor) have confirmed that board appointments flowing from a shareholder agreement are not binding unless replicated in the AoA. Moreover, directors owe fiduciary duties to the company—not the nominating shareholder—limiting the investor’s direct influence. |

| Quorum Rights | Prevents decisions in absence of investor representation. | The Companies Act, 2013 is silent on special quorum rights. However, case law (e.g., Amrit Kaur Puri) confirms that higher thresholds (like requiring investor presence) are enforceable if provided in the AoA. To avoid abuse or gridlock, best practice includes time-bound adjournment mechanisms. Still, without AoA support, these are merely moral obligations. |

| Veto / Affirmative Voting (Reserved Matters) | Grants investors control over critical decisions. | These rights are valid only if entrenched in the AoA (as per Section 5(3), Companies Act). Courts (Rangaraj principle) have struck down shareholder agreements that grant veto rights not reflected in the AoA. Veto rights on matters like capital raise, M&A, or change of business are common but must not contradict statutory provisions. They should also define thresholds and procedures clearly to avoid arbitrariness. |

| Pre-emptive Rights | Prevents dilution by offering first rights in new issues. | Statutory pre-emptive rights under Section 62(1)(a) are general. Investors usually negotiate tighter versions (e.g., participation in any future round). Courts accept stricter-than-statute rights if inserted into the AoA. SHA-only rights lack binding effect. For stronger protection, down-round safeguards and price-adjustment formulas (anti-dilution) should be included. |

| Anti-dilution | Protects valuation in future funding rounds. | Not statutorily recognized but widely accepted in practice. These clauses ensure shareholding % is preserved, typically via full ratchet or weighted-average methods. Courts treat these as contractual provisions; enforceability again depends on AoA incorporation. Full ratchets can deter future investors and must be balanced with fair valuation mechanisms. |

| Tag-Along Rights | Protects minority investors by allowing joint exit with promoters. | Enforceable if in SHA and AoA. Courts uphold such rights unless they contradict public policy. Helps investors avoid being stranded with new majority owners. Needs precise definition of triggering events and scope (e.g., % of promoter stake being sold). |

| Drag-Along Rights | Allows lead investors/promoters to compel others to sell during exit. | Enforceable with AoA backing, but courts scrutinize for fairness—especially for minority holders. Clauses should clearly define fair valuation, method of determining price, and conditions under which the drag may be exercised. If improperly exercised, it may lead to claims of oppression/mismanagement. |

| Exit Rights (IPO, Sale, Buyback, Put Option) | Ensures liquidity for investors. | Exit through IPO or third-party sale is standard. Put options, however, must comply with the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act—SEBI has historically treated them as unenforceable forward contracts unless structured carefully. Courts have occasionally upheld them if fair price mechanisms are included and no speculative element is found. |

| Information Rights | Gives investors access to financial and business data. | Investors often seek monthly/quarterly reporting, budget access, etc. Though not in the Companies Act, these are enforceable if in the AoA. Courts uphold stricter disclosure standards. However, these cannot override statutory audit/reporting rules or infringe confidentiality obligations of the company. |

| Transfer Restrictions (ROFR/ROFO) | Preserves control over ownership structure. | Indian courts have been clear (Rangaraj)—such restrictions are unenforceable if not in the AoA. Right of First Refusal (ROFR) and Right of First Offer (ROFO) are valid contractual tools but only enforceable if incorporated into company charters. |

| Founders’ Lock-in | Prevents promoter exit during early investment period. | Common in VC deals to retain founder commitment. Legally enforceable if time-bound and proportionate. Without AoA or employment agreement support, enforcement may be difficult. Courts may not enforce open-ended restrictions. |

| Non-Compete / Non-Solicit | Protects business from founder competition post-exit. | Section 27 of the Indian Contract Act voids agreements in restraint of trade. However, non-compete clauses during subsisting employment or shareholding are generally valid. Post-exit restrictions must be narrow in time, scope, and geography to survive judicial scrutiny. |

| Deadlock Resolution | Offers a mechanism to resolve investor-promoter disagreements. | Russian roulette, Texas shoot-out, buy-sell arrangements, or third-party mediation are commonly used. Courts uphold such mechanisms unless they are vague or one-sided. Should include escalation matrix and tie-breaker clause. |

| Dispute Resolution (Arbitration) | Ensures efficient, private dispute handling. | Valid under Indian Arbitration Act. However, shareholder agreement arbitration clause can’t override statutory remedies (e.g., oppression under Companies Act). Ensure all relevant parties (including company) are signatories to prevent jurisdictional issues. Specify seat, language, and institution of arbitration. |

Landmark Cases Related to Shareholder Agreement

| Case Name | Citation | Key Issue | Court’s Ruling |

| V.B. Rangaraj v. V.B. Gopalkrishnan | (1992) 1 SCC 160 | Enforceability of share transfer restrictions in SHA not reflected in AoA | Such restrictions are unenforceable unless incorporated in the Articles of Association. Set foundational precedent. |

| Madhu Kapur v. Rana Kapoor | (2016) 196 Comp Cas 345 (Bom) | Validity of board nomination rights | If the AoA provides for nomination, it must be honoured. Affirmed binding nature of AoA in corporate governance. |

| Vodafone Int’l Holdings v. Union of India | (2012) 6 SCC 613 | Interpretation of contractual rights under Indian law | Suggested SHA terms may have legal force under general contract law, but this was obiter and not binding. |

| World Phone India Pvt. Ltd. v. WPI Group Inc. | (2013) 178 Comp Cas (Del) 173 | Affirmative voting rights enforceability | Reaffirmed Rangaraj principle: affirmative rights in SHA are enforceable only if in AoA. |

| Feroz Bhasania v. United Breweries Ltd. | (1971) ILR 1 Cal 367 | Validity of contractually granted veto powers | Held unenforceable when not backed by AoA, even if agreed in contract. |

| In Re: Jindal Vijayanagar Steel Ltd. | (2006) 129 Comp Cas 952 (CLB) | Entrenchment of AoA provisions | Articles requiring unanimous consent to amend AoA were held invalid unless compliant with Companies Act. |

| Amrit Kaur Puri v. Kapurthala Flour Mills | (1984) 56 Comp Cas 194 (P&H) | Validity of custom quorum in Articles | Custom quorum clause was upheld. Articles can specify stricter requirements than the Act. |

| Uma Shankar Gupta v. Vishal Promoters Pvt. Ltd. | (2017) 203 Comp Cas 520 (NCLT Cal) | Enforceability of board quorum requiring investor presence | Upheld such clause, noting that valid AoA provisions override standard procedural assumptions. |

Conclusion

The bottom line? In Indian PE deals, the effectiveness of a Shareholder Agreement depends almost entirely on the Articles of Association. Investors must go beyond drafting watertight contracts—they must secure alignment with the company’s constitutional documents. Without this, even the most carefully negotiated rights may collapse under judicial scrutiny.

The readers may peruse the following model shareholder agreement for reference:

Pages: 1 2

Thank you for this post, it helps with the basics.